Prairie View, Texas

CNN

—

More than an hour after Beto O’Rourke had wrapped up a town hall meeting at Prairie View A&M University, three female students who had waited in a selfie line were trying to teach the former congressman a TikTok dance.

O’Rourke, the favorite for the Democratic nod in Tuesday’s primary to take on Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, was struggling. But he embraced the embarrassment.

“You know what, that’s good,” he told them after several tries. “People will like that because it’s so bad. It’s so bad!”

It was typical O’Rourke: the kind of moment that makes crowds clamor to see him in person, or mock him online; one that comes across as a breath of fresh air to some, or as a goofy dad out of his depth to others.

The question O’Rourke faces this year is whether Texas voters – who will see him as a major candidate for the third time in five years – are willing to give him another chance after his two losses. The challenge is made even more daunting by the reality that 2022 could see the toughest political environment O’Rourke has faced to date, as he takes on a well-funded opponent in a state where a lack of campaign contribution caps could make it impossible to keep up with Abbott in the money race.

O’Rourke shot to stardom with a near-miss Senate campaign in 2018 against GOP Sen. Ted Cruz. But his failed 2020 Democratic presidential primary run left his national brand badly dented in the eyes of many within the party. And Republicans argue that many of the positions he took during that run, including advocating for mandatory assault weapon buybacks, will hurt him in Texas.

Still, O’Rourke remains popular among Democrats on his home turf – building a following in Texas much larger than any other Democrat in a generation. In between his campaigns, he has remained active, campaigning for state legislative candidates and activating his volunteers when the state’s power grid failed last winter.

In an interview, he described his decision to run for governor as driven by loyalty to that following.

He pointed to activists who have registered people to vote despite Texas enacting one of the nation’s most restrictive voting laws, and to abortion rights advocates who fought a 2021 state law that blocks access to abortions in Texas after about six weeks of pregnancy.

“Everyone out there right now is trying despite the odds, and not giving in to despair and not sitting on the sideline,” he said. “That’s really inspiring to me. And the more my wife, Amy, and I talked about it, and the more we saw what other people were willing to do, the more inspired and energized we became – and the more confident we also became about our ability to win.”

“I know that I’ll be the next governor of the state of Texas, not so much because of what I do or don’t do, but because of what we all decide to do together,” he said.

The heady days of March 2019 – when O’Rourke was at the height of his popularity, launching his presidential campaign with sky-high expectations and hype from an Oprah interview and a Vanity Fair cover – are now a distant memory.

He had electrified Democrats with his 2018 Senate campaign, which he launched early and with low expectations, but burst into the spotlight with a series of viral moments. Some were serious – such as an August 2018 town hall in which O’Rourke defended NFL players who kneeled during the national anthem. Others, like clips of him skateboarding through a Whataburger parking lot, teased the possibility of generational change among Democratic Party leaders.

And the unscripted nature of his campaign – barnstorming all 254 counties in Texas, live-streaming on Facebook nearly every stop and many of the drives in between – allowed his supporters to build deep connections that would pay off in donor dollars and volunteer hours.

His campaign shattered Senate race fundraising records at the time. And though O’Rourke didn’t win, he finished less than 3 percentage points behind Cruz, a strong enough performance to exceed national Democrats’ expectations and offer a credible case that deep-red Texas could become competitive. O’Rourke’s star was on the rise, and top Democratic talent flocked to him, anticipating a presidential run.

But in 2019, those high expectations came crashing down.

Another young, White contender with a knack for viral moments had emerged as a liberal favorite in the Democratic presidential primary: Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana. And O’Rourke, who had easily defined himself against an opponent in Cruz whom Democrats viewed as a villain, struggled to find ways to stand out in a packed primary field.

His strongest moment came in August 2019, when he left the campaign trail and returned to his hometown of El Paso after a gunman who had written a racist screed complaining about a “Hispanic invasion of Texas” killed 23 people at a Walmart there. O’Rourke angrily blamed then-President Donald Trump’s racist comments and actions for the deaths.

O’Rourke’s handling of the shooting, and his advocacy for gun control measures, gave his campaign a short-term jolt. But it didn’t last. He dropped out of the race in November 2019 – months before Buttigieg would win the Iowa caucuses.

Since then, the national political landscape has changed dramatically.

Democratic candidates broke O’Rourke’s fundraising records in 2020. The coronavirus pandemic upended American life. Trump lost the White House, and his refusal to accept his loss led to an insurrection at the US Capitol and a surge in laws enacted in Republican-controlled states – including Texas – that critics say will make voting more difficult for many in 2022.

Now, O’Rourke is making his third run in five years with his party facing political and historical headwinds.

A poll of registered Texas voters conducted in late January and early February by the University of Texas/Texas Politics Project found Abbott leading O’Rourke by 10 percentage points in a likely match-up, 47% to 37%.

And even though O’Rourke has largely kept pace in fundraising since entering the race in November, Abbott, a two-term governor, currently has a massive financial advantage, with about $50 million in the bank to O’Rourke’s $6.8 million as of February 20, campaign finance records show.

In person, the O’Rourke of 2022 is much like the O’Rourke of 2018. His hair may be grayer, his hourslong post-event selfie lines may now include a ring light and his campaign may have different leadership. But the core team of road manager Cynthia Cano handling the microphone during Q&A sessions at town halls and communications aide Chris Evans live-streaming everything on Facebook and Instagram is the same. O’Rourke’s eagerness to seek out questions from those who disagree with him persists.

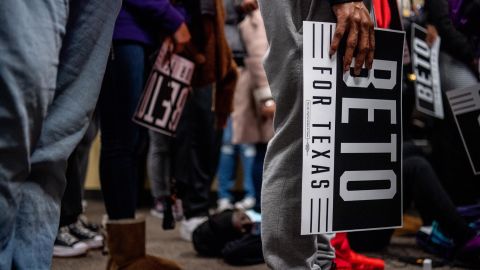

Many of his most ardent supporters in Texas remain faithful. Some of the black-and-white “Beto” signs that were everywhere in Texas in 2018 were never taken down.

But even those supporters acknowledge the uphill battle O’Rourke faces against Abbott.

Marquinn Booker, the 22-year-old student body president at Prairie View A&M, had met O’Rourke before and even told him he should run for governor. But he said there are differences between the 2018 groundswell of support for O’Rourke and now.

“The fight is still there. Support is still there. But I don’t know if it’s as big as it used to be,” Booker said. “But I have nothing but faith. His work ethic will show and prove everything that we need to see.”

Some supporters think Trump’s departure from the White House and Abbott’s embrace of more hard-line policies that have angered some Texans, including Republicans, could create an opening.

Thomas Green, an 85-year-old retiree from Houston, said he left the Republican Party six months into Trump’s presidency. He’s supported O’Rourke since then and said he is more optimistic now than he was in 2018 about O’Rourke’s chances.

“People are going to wake up to Trump, sooner or later. Can’t keep going that way,” Green said. “Abbott’s an enabler.”

In an interview, O’Rourke pointed to his volunteer army and the attendance at his events as “super encouraging” evidence that Texans are willing to give him a chance.

“The majority of people in Texas want someone other than Greg Abbott as governor,” he said. “My job over the next eight months is to make sure that I am that choice, and by ensuring everyone knows what we want to do on jobs, what we want to do on great schools, what we want to do on expanding Medicaid.”

O’Rourke’s strategy to escape a challenging political environment is simple: Blame everything in Texas on Abbott.

His argument is that Republicans have controlled every lever of state government for years, and therefore bear the blame when things go wrong.

Case in point, O’Rourke said, is last year’s widespread power grid failure, which left millions without electricity for days and was responsible for at least 200 deaths. His campaign has highlighted the grid’s failure in television ads, and O’Rourke makes it a focal point of every campaign stop. He repeatedly says Abbott is to blame for higher electricity costs, as well as looming increases for phone and internet bills, which O’Rourke blames on Abbott’s veto of legislation intended to shore up a fund that supports telecommunications for rural portions of the state.

“When he tries to blame inflation on (President Joe) Biden or socialists or anything else, we need to make sure (Texans know) the higher costs we’re paying right now are due to this governor,” O’Rourke said Friday at Prairie View A&M. “We’ve got to show up to connect the dots and be the ones to deliver the message.”

Abbott said at the time that he vetoed the legislation because the changes lawmakers sought to make to Texas’ Universal Service Fund – applying a fee to user of Voice over Internet Protocol such as Skype – “would have imposed a new fee on millions of Texans.”

O’Rourke casts Abbott and Republican leaders in Austin as focused on fighting the culture wars to appeal to the GOP’s conservative base.

“We’re focused on this really dumb, cruel stuff — like stopping a woman from making her own decision, or not making sure that we have the lights on when the temperature drops, or these culture war fights you see them engaged in — instead of the big things that all of us care about,” O’Rourke said of the actions of state Republicans.

Nious Jones, a 21-year-old Prairie View A&M student from San Antonio, said O’Rourke’s appearance Friday at the historically Black university was her first time hearing him speak.

“He’s for the people, and I like that,” she said.

But Jones, who said she will likely support O’Rourke, was more motivated by opposition to Abbott – who days earlier had told the state’s Department of Family and Protective Services that gender-affirming surgical treatments and hormone therapy provided to transgender youth should be considered “child abuse.”

“I’ve heard recently about punishing transgender kids. That was very surprising to hear. I did not expect that — especially children,” Jones said. “That was shocking.”

Source : CNN