PARIS — There is little time left until the French choose their next president on Sunday, and image is important. As media teams flutter around the two remaining candidates, President Emmanuel Macron and the far-right leader Marine Le Pen, the nation’s political cartoonists are out in force, ready to accentuate even the smallest slip.

When they pounce, many will be waiting in a country where political cartoons have deep roots, thriving as expressions of unhappiness during the French Revolution and continuing to play an outsize role in modern-day politics.

Comic books regularly top the French best-seller lists, and weekly satirical newspapers — most notably Charlie Hebdo and Le Canard Enchaîné — are considered national institutions. Last year, when Mr. Macron’s government granted teenagers 300 euros (about $325) to spend on culture, many bought comic books.

“The world of politics is very artificial,” said Mathieu Sapin, a cartoonist behind several comic books featuring Mr. Macron and his predecessor, François Hollande. “It’s very codified, which makes it deeply fascinating from a drawing perspective.”

For Mr. Sapin, the French president is a character of fascination. He is often depicted by cartoonists as a gaptoothed, square-shouldered, somewhat boyish figure. But he also remains aloof, granting significantly less access than did Mr. Hollande, who courted cartoonists as much as journalists.

“Macron is more distant with the media, though he did once come up to me to tell me how much he loved cartoons,” recalled Mr. Sapin. “He’s a real seducer.”

How much so was illustrated in Mr. Sapin’s previous book, “Comédie Française,” in 2017. In one cartoon, the two men shake hands. A bead of sweat appears on Sapin’s forehead. “This handshake is taking a long time,” reads the thought bubble.

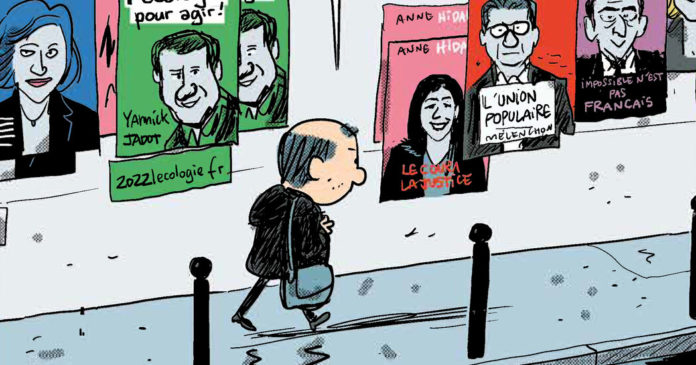

Mr. Sapin is drawing Mr. Macron for “Campaign Notebooks,” his 240-page comic book on the 2022 presidential election. The project brings together Mr. Sapin and five other veteran cartoonists: Dorothée de Monfreid, Kokopello, Louison, Morgan Navarro and Lara.

Each cartoonist was assigned one or two candidates to follow for the course of the campaign — most of whom were eliminated in the first round on April 10. For eight months, they traveled the breadth of the country, attending rallies and meetings, and even tagging along on trips overseas.

The team has worked independently, occasionally meeting in Mr. Sapin’s studio to plot on a big dry-erase board. “We are all recounting different events, but it’s all rendered in the same way,” said Louison, who goes by one name. For her, the small details are the most compelling.

“Political gaffes, the sight of an aide frantically helping a politician with their tie before a speech, backstage pep talks and spats — these make the comics,” said Louison, who followed Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, during her unsuccessful campaign, joining her on bike rides around the city.

Beyond being used as a tool for revolt, political cartoons have long been used as an ideological weapon — Communists and radically conservative Catholic groups in France used cartoons to influence the country’s youth after World War II — and their importance is not lost on Mr. Macron.

He gave the keynote speech two years ago at the International Comics Festival in Angoulême, the first presidential visit since François Mitterrand attended the event in 1985, and he announced plans for a European House of Press and Satirical Cartoons to open in the capital by 2025.

“Still,” said Mr. Sapin, “he wants to protect his image.”

His rival, Ms. Le Pen, is often drawn as a self-congratulatory figure, her mop of yellow hair and twinkling blue gaze emphasized. Mr. Navarro has chosen to home in on what he sees as a smug air, representing Ms. Le Pen with spiky, upturned features and eyes narrowed in steely determination.

Mr. Navarro has noticed some of her subtler tics, too, such as the nervous puffing on an e-cigarette, or the readjusting of a particular strand of hair. These he has worked into his drawings for humorous effect, but also a degree of pathos — something not usually associated with a far-right politician who was once depicted on the cover of Charlie Hebdo dressed in a dirndl and holding a gun to Europe’s head.

While in Marseille, Mr. Navarro was startled by the sight of Ms. Le Pen, whose message is fiercely anti-immigrant, posing for a selfie with a group of Muslim men, a moment he captured for the book. “Her image has changed, somewhat — they seemed unfazed by her reputation,” Mr. Navarro said.

What to Know About France’s Presidential Election

The sequential structure of a cartoon strip is well suited to politics, but as the team learned in the case of the far-right candidate Éric Zemmour, not everything goes as planned.

In the early days of the campaign, Mr. Zemmour was “a joke,” Mr. Sapin said, and the team didn’t even bother to assign anyone to cover him. “But then in the autumn he became a serious candidate, and we had to adapt.”

With his eccentric mannerisms and caterpillar eyebrows, Mr. Zemmour was easy prey for cartoonists — attracting comparisons to Gargamel, the villain from the Smurfs. But Mr. Navarro noticed something else: “I was surprised by how many young people were among his supporters, they seemed really fired up.”

“In the newspapers he often comes across as a caricature,” Mr. Navarro said. “But what we’re doing here is showing the context of events — not just caricaturing each candidate.”

Bringing the different campaigns together in a book affords unusual insights into strategy. Were the candidates playing the long game? Did their approaches remain the same throughout?

“And it also shows just how long they’ve all been working up to this moment,” said Kokopello, who also goes by one name and drew Valérie Pécresse, the now-eliminated, center-right Republican candidate. “Many people seem to think the campaigns started just a couple of months ago, but it’s been much longer.”

Along with the election’s twists and turns, the book chronicles the shifting national mood: In the opening pages, the pandemic dominates the narrative, face masks slowly fading from view; the emergence of surprise candidates, the failure of early hopefuls; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February.

“We are recording how things played out, in real time,” Mr. Sapin said.

The last 12 pages are still blank, awaiting a final result that will likely be close. “Anything can happen — that’s what makes it so thrilling.”

Source : Nytimes