Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times. The project began in 2018 with a focus on women, but it’s widening its lens this year.

In 1955, Satya Narayan Goenka, a successful Burmese industrialist, began experiencing intense migraine headaches. Conventional medicine didn’t provide relief, so, at the suggestion of a friend, he sought out a meditation teacher.

At the time in Burma (now Myanmar), it was uncommon for everyday people to meditate, an activity typically reserved for Buddhist monks and nuns. But Goenka took to the practice, studying with his teacher, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, for 14 years.

Then, in 1969, Goenka renounced his business, moved to India and began teaching meditation full time, focusing on a style known as vipassana, or insight meditation.

Instead of teaching monks and nuns, Goenka aimed to teach lay people, like himself. Even more, he was radically inclusive for his day, accepting students regardless of caste or gender.

His arrival in India coincided with a surge of interest in Eastern spirituality among young British and American travelers. And in a matter of months, Goenka, who spoke English, emerged as a popular teacher for Westerners, including several young Americans who would become well-known spiritual teachers in their own right.

“He was, in the early ’70s, one of the few easily reachable, doors-open teachers for Westerners,” said Daniel Goleman, the author of “Emotional Intelligence” (1995) and other books, who studied with Goenka. “He played a really pivotal role in initiating a generation of people who would become the first mindfulness teachers in the West.”

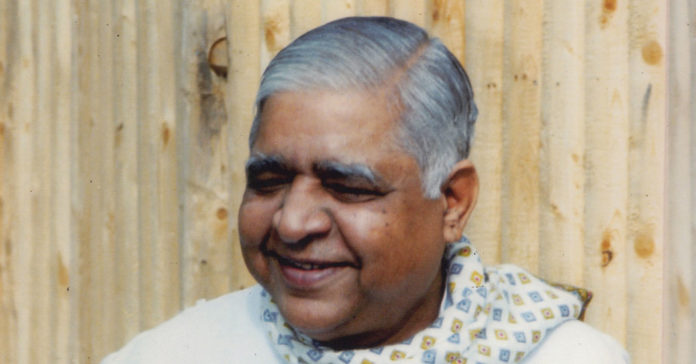

By the time he died on Sept. 29, 2013, at 89, Goenka had established a global network of more than 100 meditation centers.

Today, meditation and mindfulness are taught in businesses, schools, hospitals and prisons, and mindfulness apps have been downloaded onto many smartphones.

“His legacy is enormous,” said Sharon Salzberg, a meditation teacher who studied with Goenka in 1971. “If you have any interest in mindfulness today, it’s thanks in part to Goenka.”

Though his teachings were derived from Buddhist texts, Goenka kept the religiosity to a minimum, an approach he described in 2000 at the Millennium World Peace Summit, a large gathering of religious leaders at the United Nations.

“Rather than converting people from one organized religion to another organized religion,” he said, “we should try to convert people from misery to happiness, from bondage to liberation, and from cruelty to compassion.”

Born in Mandalay, Burma, on Jan. 30, 1924, Goenka was raised by an affluent Hindu family of Indian descent.

When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, during World War II, Goenka and his family fled to India. Upon their return home, he came to lead a family-run conglomerate of businesses in exporting, textiles and agriculture. At 30 he was elected head of the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce.

But material success did not make him happy, and by his own admission he had been short-tempered and egotistic.

After he began meditating, Goenka embraced the teachings of the Buddha, though he was never ordained as a monk. His teacher, U Ba Khin, was also a layman, who worked as a Burmese government official. Before his move to India and his break from the professional world, Goenka taught meditation part time and continued to oversee his business for more than a decade. He had six sons with his wife, Elaichi Devi.

“He was really representative of a lay person’s lineage,” Salzberg, his student, said. “He was very much a spokesman for the possibility of having a profound practice even while you stayed in the world with responsibilities.”

Salzberg went to a retreat led by Goenka — her first — in January 1971, in Bodh Gaya, India, the town where the Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment. On that 10-day retreat alone there were at least five Americans in addition to Salzberg who would go on to become influential meditation teachers; others included Ram Dass, Krishna Das, Joseph Goldstein, Mirabai Bush and Goleman (who went on to write extensively about emotional and psychological issues for The New York Times).

Salzberg said Goenka’s meditation style was intense and austere. Long periods of silence were only occasionally interrupted by Goenka’s teaching and chanting. Sitting with one’s legs crossed for 10 days can bring on cramps and soreness, and the retreats could be physically painful and mentally challenging. But with simple instructions that involve paying close attention to the breath and other physical sensations, Goenka taught students how to cultivate a profound understanding of impermanence and an abiding sense of compassion.

“The first night of the retreat he said, ‘The Buddha did not teach Buddhism — he taught a way of life,’” Salzberg recalled.

Goenka established his first meditation center in 1976. But demand for his teaching soon outmatched his availability, and in 1982 he began training assistant teachers who could establish their own centers.

“He was very keen that as many people as possible get the training,” said John Beary, who began studying with Goenka in 1973 and was one of the first assistant teachers; he now teaches at a California center.

The instructors, however, were not empowered to develop their own methods. Goenka instead had them play recordings of his instructions and be available to students only for questions or clarifications.

Though the model was unusual, the endeavor was a hit and has continued to grow since his death. Today, there are some 200 centers around the globe, in places like Kaufman, Tex.; Helsinki, Finland; and Western Cape, South Africa, with more opening each year. A central organization in India oversees the centers, which do not charge for the courses and rely on volunteer teachers. Donations support the operation.

As Goenka grew more popular, he wrote books and began traveling and teaching internationally. A documentary film, “Doing Time, Doing Vipassana,” chronicles how Goenka’s teachings transformed inmates and guards in India’s largest prison. Beary estimates that over the years more than 1 million people have taken one of Goenka’s 10-day courses.

“Develop purity in yourself if you wish to encourage others to follow the path of purity,” Goenka told a group of his students in 1989. “Discover real peace and harmony within yourself, and naturally this will overflow to benefit others.”

Source : Nytimes