When I would tell people that drawing saved my life, I thought I was being hyperbolic. Then the coronavirus hit. Drawing had helped me survive another very dark period of my life, earlier. Could it now be helping me to stay healthy?

I know it is keeping me sane, as it did five years ago when I was out of work. I had been an editor at The New Yorker for more than two decades. The internet changed my job slowly and then quickly, and then I was out.

Frustrated and adrift middle-aged men who lose their jobs in shrinking industries are not just a danger to themselves, they are capable of putting everyone at risk. I knew I had to do something, fast, and I tried neurofeedback.

I spent about a year and a half with wires strapped to my head while listening to classical music and staring at undulating bar graphs on a computer. It was odd, but I felt calmer. That could have been placebo effect, but I also experienced a physical change. A few months after starting, I noticed my eyes filling with tears, and I started crying for the first time since junior high. I didn’t cry when my dog died as a teenager or when my father died, 12 years ago. But there I was, tears running down my cheeks in a darkened office on West End Avenue.

Neurofeedback helped me manage the stress of losing my job, but my severance package wasn’t unlimited and I had to give up the therapy, which was expensive. At that point, I had been drawing casually for years, practicing on my commute to work.

Suddenly spending more time drawing was easy because I was out of work. Or I should say necessary because I was out of work, which meant I was left taking care of my kids, then in elementary school, as well as the laundry, the food shopping and the housecleaning while my wife went to her office.

I found that drawing even the most mundane thing like a pair of shoes helped me relax. If it looked like we were going to be late for a doctor’s appointment or a soccer game, for example, I was less likely to get frustrated if I took a moment to capture the curving metal of the radiator in the living room or the backpack that was sitting in the hall. While I waited for everyone to get ready, time seemed to expand and slow. There was quiet in the house, and in my soul.

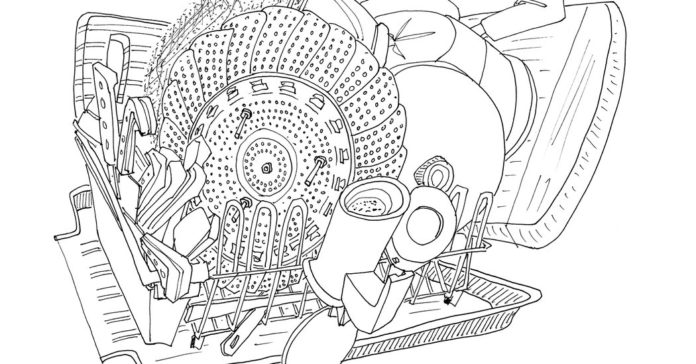

I liked to cook and was comfortable spending time in the kitchen, so I started drawing my dish rack every night. I now have more than a thousand renditions of my dish rack. Sometimes, especially during the lockdown, depending on how stressful things are, I draw it two or three times a day. These days, if I’m irritable at home and getting on my wife’s nerves — which is still a constant risk, for my recent personal growth has been matched by my children running smack into their teenage years — she’ll say to me, “Do you want to go do some drawing?” or “Have you done your dish rack yet, dear?”

By the time I’m done with a sketch, it is as if I’m a new man. This is partly because drawing has taught me to make the most of my mistakes. I work in ink, from life. It is as if every line is already out of place from the start. It is oddly liberating, as I have learned to forgive myself. I draw not for the result but for the process, and fortunately I’ve been doing it long enough that the results are pleasing. I love capturing the three-dimensional image on the two-dimensional page. If Wordsworth’s heart leapt up when he beheld a rainbow in the sky, mine jumps when I convincingly foreshorten the handle of a frying pan, and it rises off the page.

There’s scientific evidence for the health benefits of a drawing practice. A 2016 study at Drexel University found significantly lower levels of cortisol after 45 minutes of making art. The body typically releases cortisol, a hormone made in the adrenal gland, in response to danger, which is great if you are being chased by a lion or a tiger.

“However, if you are constantly feeling stressed, which is perceived as a threat by your brain, your cortisol levels will consistently be high,” Girija Kaimal, the author of the study, said. “If you’re constantly on high alert, it puts a lot of pressure on your heart. It takes away resources from your digestive system. A series of chronic health conditions can develop if you’re not able to feel relaxed and not able to regulate down the cortisol in your body.”

Making art has other advantages. In a 2017 study, Dr. Kaimal demonstrated that coloring, doodling and free drawing activate the medial prefrontal cortex, the seat of so-called executive function, and improve self-perceptions of problem solving. It doesn’t take much effort to yield results. A 2019 study by Jennifer Drake at Brooklyn College found that a mere 10 minutes of drawing improved participants’ moods. And skill or talent are not factors: All the studies mentioned involved a random selection of people, not artists per se.

In fact, it’s not just making art that improves health and mood. Almost any hobby or act of leisure helps. A 2013 study at Pennsylvania State University found that gardening, sewing, completing puzzles and other relaxing activities lowered blood pressure. A 2015 study at the University of Merced revealed that individuals who engaged in leisure reported improved moods and less stress and exhibited lower heart rates.

What matters is how we engaged we are in the activities. “The thing that came out in the studies was this: ‘How much are you able to get outside of your head?’” Matthew J. Zawadzki, the lead author of the studies, said.

“You don’t need to be a perfect drawer to enjoy the activity or to reap the mood benefits,” Dr. Drake pointed out. All you really need is a pen and paper and a bit of time. “Doodling is one thing that somehow has escaped that stigma of whether I’m skilled or not,” Dr. Kaimal said.

“It’s important to let go of any fear that might be holding you back from engaging in the hobby,” Dr. Drake said.

Dr. Zawadzki has a tip that evokes the medical value of a hobby. “Write yourself a prescription that says, ‘I’m going to take 10 minutes, three times a week. That is my time,’” he suggested. “When we come back from doing leisure, we’re often re-engaged, we’re better able to concentrate and we’re in a better mood, so the first thing is to give yourself permission to do it.”

If you do make a practice of your hobby, who knows what you’ll accomplish. For the past three years, I’ve drawn at least twice a day — first thing in the morning, and again before I go to bed — and,when I’m lucky, and now that I’m sheltering-in-place, as many times as I can in between. As a result of the peace of mind it brings me, I found a whole new career as a grant writer for a Brooklyn-based human-services nonprofit. I started selling prints of my work to people all over the world, landed a three-book deal with a major art-book publisher, and spent the past two summers in Paris and London sketching.

I knew that drawing could change my mood. When I started doing it on a regular basis, I discovered it could change my life. It may now be keeping me out of the hospital, or more.

Source : Nytimes