For a while, the story of Luka Doncic seemed like a myth: the tale of a blond basketball demigod with supernatural mental and physical powers, a 6-foot-8 Slovenian teenager whose name was whispered only in the nerdiest corners of the NBA internet. While his highlights occasionally trickled across the Atlantic, circulating among draft obsessives like contraband, they never made waves beyond those circles. Outside of Europe, Doncic (pronounced dawn-chich) was still an abstraction, a set of inscrutable numbers paired with a name. Then in September, he came face-to-face with Kristaps Porzingis — and his fabled existence suddenly felt real.

Last year national teams across Europe met at EuroBasket, a tournament that draws NBA veterans back to their home countries. Doncic, then 18 years old, joined Slovenia’s team, which was led by Miami Heat guard Goran Dragic. When Slovenia played Latvia in the quarterfinals, Doncic and Porzingis went shot for shot. Then, halfway through the fourth quarter, the two crossed paths — and for a moment, time stopped. Doncic dribbled between his legs, sizing up the towering Knicks center like a mathematician staring at a problem scrawled on a blackboard. Porzingis extended one rubbery arm. After a seemingly interminable pause, Doncic, known locally as Wonder Boy, dashed past the future All-Star and made a one-handed layup, glancing back at Porzingis as he jogged away.

The arena exploded. “I wanted to kill him,” Porzingis says with a laugh, adding that he was “never that consistent” at Doncic’s age. “I don’t know any other European kid that plays at such a high level.”

In truth, Doncic isn’t just outplaying the other teenagers in Europe — he’s also outplaying most, if not all, of the adults. He signed with Real Madrid at age 13 and made his EuroLeague debut at 16. Now, at 19, he is averaging 22 points, 7.6 rebounds and 7 assists per 36 minutes (through April 5), leading the second-best league in the world in player efficiency. Every month, throngs of scouts trek to Spain, hoping to glean new pieces of data that will help them calculate whether Doncic’s worth matches his hype. “Our reports are that he’s the kind of guy who’s very rare,” one NBA executive says.

On June 21, Adam Silver will likely announce that Doncic has been selected near the top of the draft. If, as expected, Wonder Boy lands in the top three, he’ll become the first European player to do so since Andrea Bargnani was picked first in 2006. (Porzingis, who was famously booed at his draft, went fourth in 2015.) When this happens, some fans will inevitably protest; they’ll bring up Bargnani and Darko Milicic and Nikoloz Tskitishvili, those cautionary tales that haunt European prospects like family secrets. They’ll call Doncic soft, comparing him to players who superficially resemble him, and they’ll bemoan the decision to choose him over a blue-chip NCAA prospect — even if, as Porzingis contends, “there’s no other college kid that’s able to put up those numbers in a EuroLeague game.” At the moment, Porzingis explains, there’s more hype around the Americans.

But that’ll change soon enough, he says.

Luka Doncic and Goran Dragic reflect on playing together in EuroBasket 2017 and how much Doncic has grown as a player.rancesco Richieri/EB/Getty Images

Real Madrid’s sprawling campus, called Ciudad Real Madrid, sits about 14 miles north of the city. On a Monday morning, the only people walking the property are security officers; the grounds are so quiet you can hear lawn mowers rumbling over distant soccer fields. The organization, famed for its privacy, shields its athletes from the outside world like hothouse flowers. Its players rarely give interviews before they turn 18.

After practice, Doncic emerges from the gym in sweats and Jordans, tailed by Alyson, his American publicist, and Julio, a communications staffer from Real Madrid. In street clothes, his build is surprisingly dense; if Doncic had been born in Birmingham, Alabama, instead of Ljubljana, Slovenia, he might’ve played football. He shaved off his stubble in the days since his last game, and he looks apple-cheeked and angelic, like a boy in a Renaissance painting. When I point out the change in his appearance, Doncic, who speaks a fair amount of English (his Spanish is flawless), blushes.

“I seem like a baby without the beard,” he says.

Julio, dressed in a suit jacket with a tiny scarf knotted tight around his neck, a paperback copy of Winston Churchill’s The Second World War in one hand, scurries to keep up with his charge. Doncic leads us to his car, an electric blue Porsche Panamera (“the most beautiful car in the world,” he jokes) with custom black rims. Before he turned 18, the legal driving age in Spain, his mother used to pick him up from practice.

After stopping at a gas station — Doncic ducks into the convenience store and pops out with an armload of Snickers bars for us — we drive into Madrid. As Doncic careens around a turn, Julio shudders and rubs his glasses. Doncic glances at him and grins; like most teenagers, he has a gift for trolling the adults in his presence. “I’m gonna switch to racing,” he deadpans. He swipes through a few rap stations until he finds one playing reggaeton, then cranks it up. “Why are you torturing us?” Julio says. A few minutes later, Doncic sings a few unprintable lyrics from Migos’ “Bad and Boujee.” And when Julio sighs, Doncic smiles sweetly, gesturing toward me. “I listen with the American people,” he says.

Traffic slows as we cruise through the center of the city, and some of the pedestrians stare at Doncic’s car. He points out a Five Guys, the American fast-food chain. “It’s amazing,” he says. Two summers ago, Doncic spent two weeks in Santa Barbara, California, at P3, a sports science and workout facility that draws many NBA stars. The town reminded him of a Spanish village, he says. On the weekends, he took trips to Los Angeles with his mother and his girlfriend, who had flown in from Slovenia, visiting Hollywood Boulevard, Rodeo Drive (he was impressed by the giant Nike store nearby) and Six Flags. “LA is amazing for me. I especially like the amazing cars,” he says. “I was at Venice Beach for … what was the serial there, Baywatch? And it was amazing.”

Aside from that trip, his only exposure to the States has been through American television. After watching all 10 seasons of Friends last summer, he’s working his way through How I Met Your Mother and is keen on visiting New York. “Central Park!” he says. “Drink coffee!” He knows a couple of New York Knicks: Porzingis and Willy Hernangomez, who used to play for Real Madrid (in February, he’d be traded to Charlotte). Doncic says he mostly communicates with Hernangomez while playing the video game Call of Duty.

“I tried to play Call of Duty, and I got killed in one minute,” Julio says.

I ask Doncic whether he plans on adopting a nickname like Porzingis’ Three Six Latvia, and he smiles mischievously. “Swaggy L,” he says.

Both Julio and Alyson groan.

“Swaggy … LD,” he suggests.

Doncic parks his car in a garage, then leads us to one of his favorite restaurants in Madrid: the Hard Rock Cafe. He folds his massive frame into a seat in the corner, across from a rack of televisions playing Kiss videos. Julio and Alyson sit across from him, and his Spanish agent, a former Real Madrid player named Quique Villalobos, sits at a nearby table. A waiter approaches, wearing suspenders sagging under the weight of a dozen buttons. Doncic, speaking in Spanish, orders the Famous Fajitas (they’re amazing, he tells me) and a plate of nachos. “Con doble queso,” he says.

After his food arrives, I ask Doncic if he ever hears from NBA fans on social media. He nods, blushing again. “Some of them write ‘Tank for Luka,'” he says. “I don’t know. I just laugh.” When he looks at their handles, he can tell they’re from cities like Chicago, Orlando, Phoenix, Dallas — places he’s never seen, much less pondered as part of his adult life. He’s reluctant to talk about his future. Real Madrid’s season is only halfway over, and some of the team’s fans still believe he’ll stay another year. “You never know what can happen in the future,” Doncic says, stealing a glance at Julio, who is staring at his phone. “I want to concentrate on where I am.”

While Doncic is exceptionally vibrant on the court — his games are punctuated by raucous celebrations and passionate fits, one of which recently resulted in an expulsion — he betrays little emotion off of it, especially when pressed to discuss his own accomplishments. He’s quick to deflect serious inquiries with dry humor.

Villalobos describes him to me as guarded, the polar opposite, he says, of Dragic (the players use the same agency). I ask him how they’re dissimilar.

“I’m prettier,” Doncic interrupts.

Villalobos rolls his eyes. “He’s much more private,” he says. “Goran? He shows love immediately. Luka needs to know you for five years.”

While we’re talking, Alyson calls Dragic, who has stayed in touch with Doncic since EuroBasket, mentoring him as he prepares for the NBA. Seconds later, his beaming face appears on her phone. She hands it to Doncic, who prompts his friend to take off his hat and show him his new haircut. They chat in Slovenian for a minute, and Doncic bursts into laughter. After he hangs up, I ask him what Dragic told him.

“He said, ‘We’re losing in Miami, so you can come,'” he says.

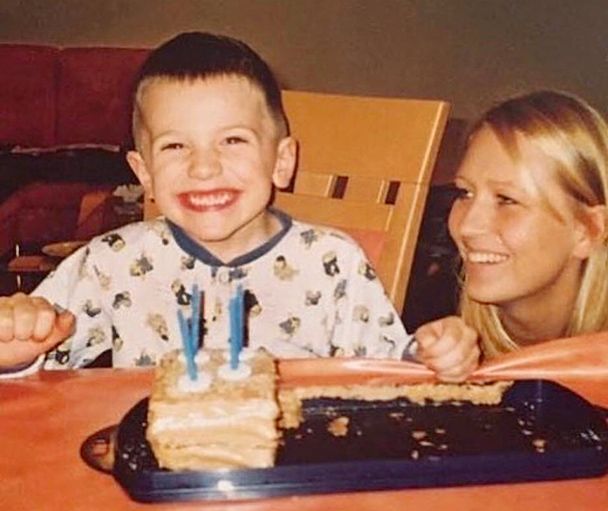

Doncic’s mom, Mirjam, says her son is very mature, but “at home, he’s a teenager.” Courtesy of Jerjne Poterbin

The first draft pick to go straight from Eastern Europe to the NBA was a Bulgarian named Georgi Glouchkov, a hulking forward known as the Balkan Banger who flamed out of the league after one season, 1985-86. For years afterward, the stereotype of European basketball players as slow and weak persisted, even as Toni Kukoc, Drazen Petrovic and Vlade Divac thrived in the NBA. Then in the early 2000s, the success of Mavericks draft pick Dirk Nowitzki spurred a run on foreign recruits: In 2003, NBA teams drafted a then-record 21 international prospects. At the time, league executives now concede, they were casting around blindly; many teams lacked the infrastructure to evaluate foreign players, as well as the savvy to help them ease into life in the States. While some of the players who came over became genuine stars, like Manu Ginobili and Pau Gasol, the botched draft picks cast an oversized shadow. Kwame Brown’s failure doesn’t hang over American prospects the way Milicic’s story lingers for Eastern Europeans.

Years passed. Prospects improved. In 2013, Giannis Antetokounmpo and Rudy Gobert entered the league; a year later, Dario Saric, Jusuf Nurkic and Clint Capela were drafted. The recent surge in European imports is no accident, according to Maurizio Gherardini, a former assistant GM in Toronto who is now the GM of Fenerbahce, Turkey’s EuroLeague team. “It reflects a progressive change in approach — NBA clubs are ready to absorb the talent coming in,” he says.

Others point to an evolution in the NBA itself. “I think it helped that along the way, the rules changed,” Nowitzki says. After the league outlawed aggressive, physical play, the NBA’s focus moved from power to finesse, shifting closer to the international game. “All of that obviously plays into the hands of some Europeans,” he says.

Even so, some teams are still apprehensive about picking Europeans near the top of the draft. While few would admit to typecasting foreigners, it’s undeniable that they’re more familiar with college stars. One executive speculates that his peers are more afraid of picking a European bust than an American one, simply because people will make a bigger deal out of it. Another says it can be hard to persuade owners, who are quick to bring up names like Bargnani. “It’s like not seeing a movie because you saw one five years ago that sucked — and you haven’t seen one since,” the executive says. “If they follow college basketball, they’re so much more comfortable with the known.”

Doncic has been a huge part of his professional team’s production this season. Salih Zeki Fazlioglu/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Ironically, Doncic might be the most known quantity in basketball. “He’s been seen, studied, evaluated by everyone,” says Gherardini, who jokes, “I was aware of him since he was born!” Given his age, Doncic’s production is almost unprecedented; rotations in the EuroLeague run deeper than they do in the NBA, which makes it hard for young players to tally meaningful minutes. (Several executives told me that the typical EuroLeague team would crush collegiate competition.) According to ESPN’s Kevin Pelton, Doncic has the highest wins above replacement player (WARP) projection of any European prospect since 2006, when data became available. Based on Pelton’s calculations, which take into account age and how other European prospects’ statistics have translated to NBA production, Doncic’s WARP projection isn’t just higher than Ricky Rubio‘s and Nikola Jokic‘s — it’s also the highest projection on record, even besting that of a young Anthony Davis.

By the numbers alone, Doncic is practically a sure thing.

But among league insiders, the question isn’t whether the Slovenian teenager will bust — almost no one thinks that. Rather, it’s whether his ceiling is high enough to justify drafting him above the likes of Deandre Ayton and Marvin Bagley III. While Doncic is hardly plodding, he isn’t exceptionally quick or strong. “His body is physically mature, so you worry about how much more it can change — how much upside he can have,” says one front office staffer. When teams have sent their best athletes to stop him, he’s struggled at times to break free. On the other side of the ball, he’s a diligent defender, but he isn’t agile enough to keep up with nimble guards.

And yet, when NBA insiders criticize Doncic’s game, they’re quick to add that they’re nitpicking. He might be limited on defense, but he can still play multiple spots on the floor, sliding seamlessly into the league’s amorphous lineups. When Doncic has the ball, it feels like he’s been given a flashlight while everyone else on the court is fumbling in the dark; he sees passing angles before they materialize, making him deadly in the pick-and-roll. “His game is much older than his age,” explains one front office higher-up. “All of the stupid clichés you’re gonna hear? It’s because they’re all true.” Doncic’s shooting percentages have declined over the course of the long season — 31 percent from 3, 47 percent overall through April 5 — but his mechanics are sound, suggesting fatigue and shot selection might be undermining his natural ability.

In December, during a EuroLeague game against Belgrade’s Crvena Zvezda, Doncic doesn’t seem tired, but his lack of speed shows up at times. When he hustles back on defense, he lumbers a bit, footsteps thudding on the floor. It would be absurd to call him unathletic, but he isn’t graceful; he uses his body to carve out space like a person butting into a conversation.

Then, just when one is tempted to make too much of this apparent lack of finesse, something clicks. Real Madrid weaves together a series of screens and Doncic cuts inside, then sinks a jumper. A couple of possessions after that, he disrupts a shot and sprints across the court, dunking off a lob and dangling from the rim for a moment like a fish wriggling on a hook. (“He likes doing that,” murmurs his agent, Bill Duffy, who is sitting to my left.) Seconds later, he shakes a defender and hits a step-back 3, then a pair of free throws, then one more 3-pointer.

In five minutes, Doncic has scored 12 points.

When the second quarter begins, Doncic’s scoring slows, and the howling in the arena subsides — until he pulls off a move so astonishing, I didn’t realize what actually happened until I returned to the States and re-watched the tape. A few minutes in, he dribbles behind the arc, where he’s double-teamed by a pair of Serbian team defenders. They close in on him, raising their arms like children pretending to be mummies. When Doncic tries to elude them, he falls backward and, in the process of tumbling, lobs the ball more than 25 feet to an open teammate in the low post, setting him up to score.

The announcer giggles. There isn’t much to say.

Source : ESPN